The Prohibition of Gaelic Names

At a quarter past midnight on 17th June 1934, Bella Munro of Auchindrain gave birth to a baby girl. She and her husband Malcolm “Cally Stoner” Munro had been married just over two years and were sharing the house we know as building H, Stoner’s House, with Cally’s aged father, Duncan.The baby was born at home, so it must have been a disturbed night for all.

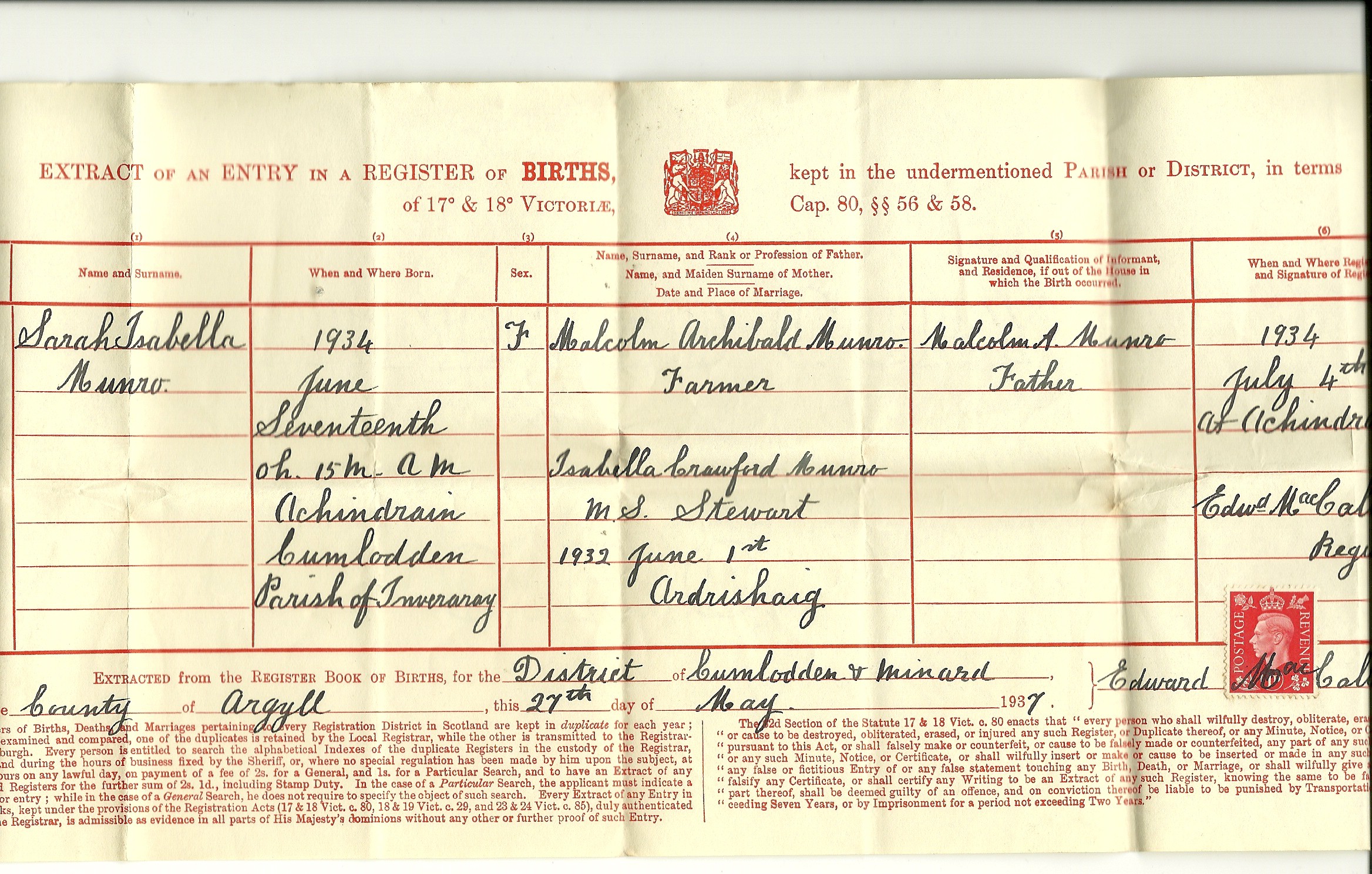

Cally and Bella named their daughter Morag. She was the first baby born at Auchindrain, in possibly twenty years. There seems to have been no rush to register her birth – the registrar, after all, was Cally’s childhood friend Eddie MacCallum and he lived only a couple of minutes’ walk away within the township. Indeed, it was seventeen days before Eddie sat down to write out Morag’s birth certificate. But that was not the name he recorded. The certificate says “Sarah”.

As Morag herself told us when she came back to the township to visit in 2011, when her father Cally first went to register her birth, Eddie MacCallum’s response was that she could not be called Morag, because that is a Gaelic name and Gaelic names were not allowed by law. Perhaps now we have a reason for the delay in registration, whilst Cally, Bella, and maybe Eddie discussed what she was to be called instead. Usually, we understand, registrars recorded the officially recognised English version of a child’s Gaelic name, but the equivalent of Morag seems generally to have been “Marion”, so why “Sarah”? We will never know for certain, but Morag’s grandmother, Bella’s mother, was Sarah, so perhaps that was the agreed compromise. Either way, throughout her long life Morag has always been called “Morag”, never Sarah.

This isn’t just an isolated story of how one little girl’s name was stolen from her, how Mórag Nic an Rothaich became Sarah Munro. The practice of the law and official systems refusing to recognise the existence of Gaelic went back two centuries. It was rooted in a view that Gaelic was a “barbaric” language, and that if the Gaels were to become civilised they had to learn and use English instead. We don’t yet know exactly when the law was changed to allow Gaelic names, but it was certainly well into the 1960s, possibly even later. In today’s world, where Gaelic language and culture is seen as being for now and for the future rather than just something of the past, it is hard to imagine how different this once all was – and still within living memory.

Suas le Gáilig Arra-Gháidheil!